The average overweight American looking to lose weight will set a goal of 16% body weight loss, or around 30 lbs. Most people will never come close. I wanted to find out if anything actually works.

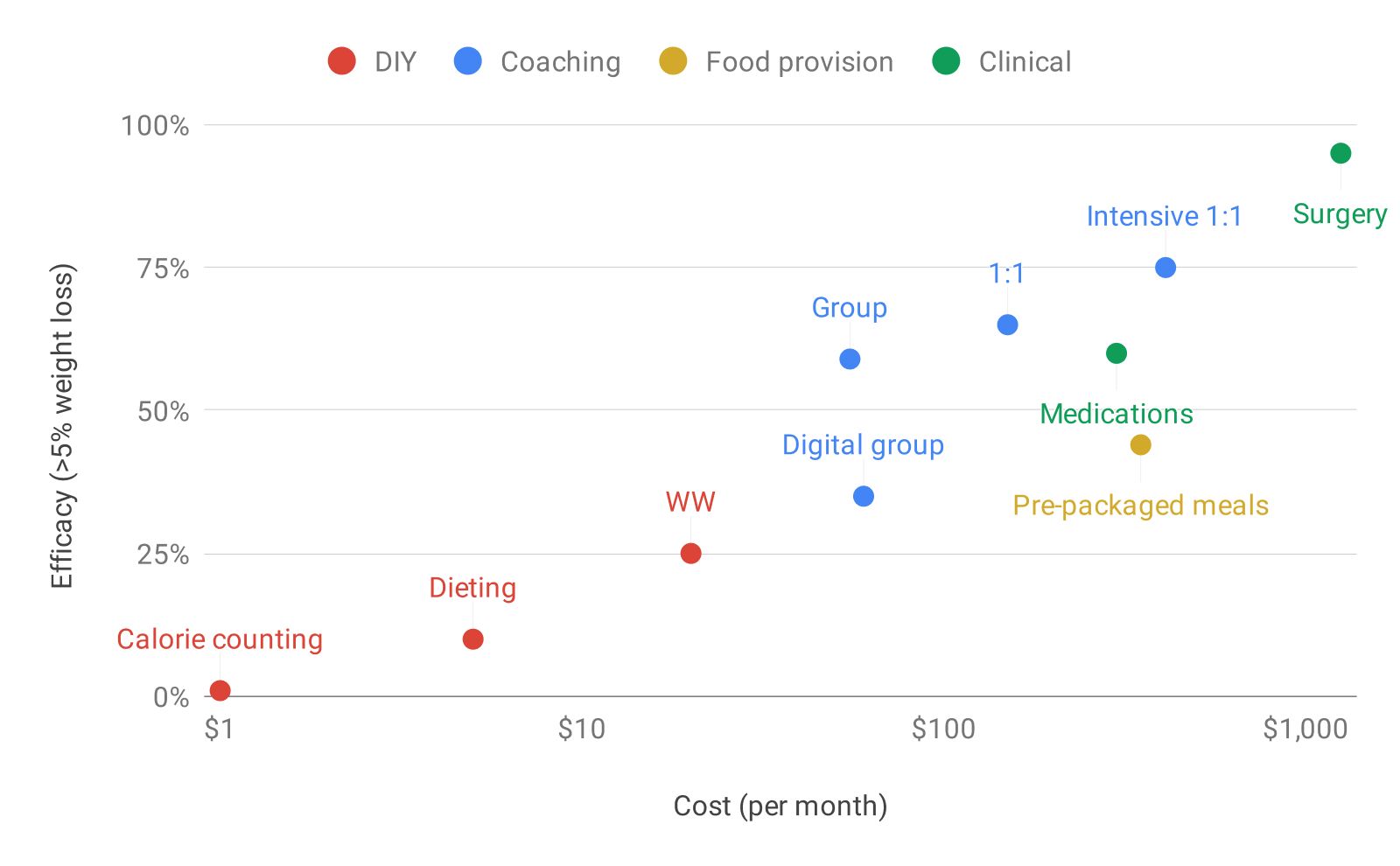

I looked at over 100 peer-reviewed studies and grouped the different kinds of interventions I examined into the following categories:

- Do-it-yourself: using tools like calorie counting or resources like diet plans to try to make lifestyle changes on your own

- Coaching: interacting with a lifestyle coach in a group or 1:1 environment, virtual or digital

- Food provision: using pre-packaged, portion-controlled meals as a significant part of your diet

- Medications and surgery: using weight loss medications to help manage appetite and maintain a calorie deficit, or receiving bariatric surgery to restrict the amount of food the stomach can hold

Over 70% of Americans are overweight or obese, and that proportion is expected to reach 75% in a decade. Over half of this group report trying to lose weight, and billions of dollars are spent every year on weight loss products and services. Since it doesn’t seem to be helping, I assumed that:

- Weight loss efficacy must be quite poor for almost all interventions

- Spending money doesn’t matter (perhaps with the exception of surgical intervention). If anything, more money probably means a higher likelihood of being scammed.

Both of my assumptions were wrong.

- There are a variety of weight loss interventions that can work quite well

- They line up roughly along how much they cost - the more expensive the intervention, the better it performs (and this relationship tends to hold even within an intervention category)

0) Losing at least 5% body weight is the benchmark

Before breaking down the interventions, let me define what I’m actually looking at. Most obesity research articles will report at least one of two measures if they're investigating a weight loss intervention:

- Average body weight percent lost

- Proportion of people who achieve greater than 5% body weight loss

5% body weight might not seem like much, but we know that it’s a physiologically significant change that can reduce your risk of developing type 2 diabetes by almost 50%, and can improve cardiovascular markers like blood pressure and cholesterol as well. In fact, many insurance companies and Medicare will provide bonus compensation to programs that are able to help patients lose at least 5% body weight.

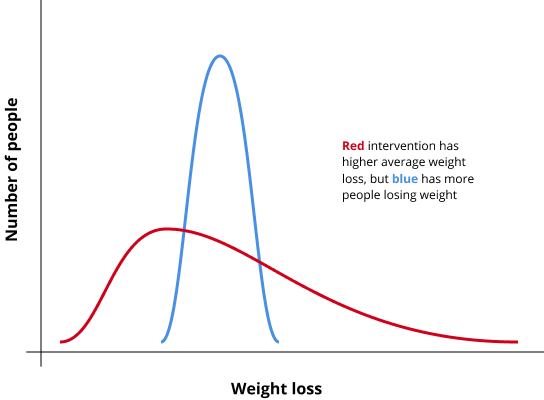

The 5% threshold also helps normalize between study populations and allows us to better understand the distribution of results from an intervention, or what an average person might expect. I didn't want to end up equating an intervention that produced magical results for a small minority of people with another intervention that helped a majority lose a reasonable amount of weight.

Most studies query weight loss at 6 or 12 months, and frequently don't include follow-up after that. So, let's assume that the efficacy of a weight loss intervention is defined by the proportion of people who lose 5% body weight or more at 12 months.

1) Do-it-yourself is the hardest route

This is the most popular weight loss approach, and it's driven by two large camps:

- Calories-in calories-out (CICO): "it's all about eating less than you burn"

- Specific diet: "low-carb/keto/paleo/intermittent fasting/whole 30 is the best way to lose weight"

Most people who try to follow a CICO-type approach will regularly log their food and count calories, using a tool like MyFitnessPal to help keep them on track. One study from 2014 (n = 212) found there was no statistically significant difference in weight loss between control (no guidance) and patients who were instructed to use MyFitnessPal.

You can pay for help with CICO as well. WW (previously known as Weight Watchers) is one of the most well-known brands in the weight loss industry, and a core component of its program is their points system. Program participants are given a daily and weekly points budget, and asked to count how many points they've eaten by logging their food. Each point roughly corresponds to 50 calories.

In a study funded by WW (n=180), researchers found a statistically significant difference between WW and control: 25% of participants lost at least 5% body weight while using WW for free, compared to 13% of control.

Why was the WW result better than MFP? The WW app at the time of the trial (2013) was similar to the MFP app (the WW app now has a social network/feed as well), and the activity of food logging is comparable. I guess the WW brand and using points instead of calories is sufficient to help twice as many people hit the 5% mark compared to control.

Measuring the weight loss efficacy of a specific diet isn’t easy (e.g. how do you ensure adherence while maintaining real-world applicability?), but many studies have attempted to do so. Here are a few which looked at weight loss at the 12 month mark:

| Study | Result |

|---|---|

| Low-fat vs. low-carb (<20 g carbs/d) (2003, n=63) | No significant difference |

| Atkins (low-carb) vs. WW vs. Ornish (low-fat) (2005, n=160) | No significant difference |

| Low-fat vs. low-carb vs. Mediterranean (2008, n=322) | Low-fat significantly worse |

| 4 different macronutrient diets, ranging from 35 to 65% carb (2009, n=811) | No significant difference |

| Low-fat (<20 g fat/d) vs. low-carb (<20g carbs/d) (2018, n=609) | No significant difference |

| Alternate-day fasting (25% calorie budget on fasting days, 125% on feasting days), normal calorie restriction (75% calorie budget every day) (2017, n=100) | No significant difference |

Given the fervor of many diet proponents, this result may be surprising - I would have expected consistent and significant differences between diets. But when you consider the fact that with every approach, a minority of people (<20%) find the diet highly effective and lose meaningful amounts of weight - and you also consider the general difficulty of weight loss - it makes sense that you can find champions of virtually every legitimate dieting approach.

In this regard, saying that “diet X is the best way to lose weight” is probably not a globally-correct statement given the evidence so far. Instead, it should be the much less interesting: “no diet performs meaningfully better on average, but there exists some diet that is the best way to lose weight for you.”

2) Coaching helps, and it can scale

Most people who try to lose weight never try coaching, since it’s typically expensive and takes considerable time and motivation. I assumed the literature would suggest that coaching was uneven in quality and largely dependent on the experience and skill of the coach. That very well may be the case when working with the average nutritionist or dietitian, but it turns out that weight loss coaching can scale.

The Diabetes Prevention Program (DPP) was a landmark study funded by the National Institutes of Health that demonstrated you could get people to lose weight through standardized coaching. With a 16-week core program and monthly sessions afterwards, the original 2001 trial (n=3234) resulted in 65% of participants losing at least 5% body weight, reducing the incidence of type 2 diabetes by 58%. Other coaching programs, some of which draw heavily on the DPP curriculum, show similarly effective results.

| Approach | Cost per month | Efficacy (>5% weight loss) |

|---|---|---|

| Omada Health DPP: app-based group coaching | $60 | 35% |

| HELP-PD DPP: group coaching with community members | $55 | 60% |

| Original DPP | $150 | 65% |

| LookAHEAD DPP: group coaching with liquid meal replacements | $233 | 70% |

| Virta Health: intensive type 2 diabetes management + keto diet | $410 | 75% |

The HELP-PD study trained coaches who were members of the community with well-controlled type 2 diabetes; they had no prior coaching experience or certification. Apparently 36 hours of coach training was sufficient to get 60% weight loss efficacy - and that isn’t really much lower than the original DPP study’s 65% mark, which relied on dietitians or master’s degree-trained coaches. If you believe that these results generalize, then the average person probably doesn’t need a highly-trained, highly-experienced dietitian to receive effective coaching and lose weight. Presumably equipping empathetic people with the right curriculum will get you most of the way there.

3) Food provision is expensive and difficult to stick with

Restricting intake is the underlying principle behind every weight loss approach, and sticking to pre-portioned, pre-packaged meals is another way to do it. Jenny Craig, Nutrisystem, and Medifast sell bars, shakes, frozen meals, packaged soups and pastas - and they sell fast results.

All of these programs have participants eating 800-1200 calories per day, or around 30-50% of what they might normally eat per day. These meals aren’t cheap: a month’s worth of Jenny Craig meals costs $600 per month, and since the average American spends around $250 on food per month, that’s an additional $350!

A 2010 paper (n=442) provided Jenny Craig prepared foods and counseling to participants for free, and observed that over 60% lost at least 5% body weight - a pretty strong result. It wasn’t clear how well this applied to real-world settings though: one of the hardest parts of sticking to a prepared foods program is the cost, and the study took that out of the equation. Another paper I found confirmed this intuition: based on the raw data of Jenny Craig participants in 2001, only 44% of participants hit the 5% weight loss mark.

4) Medications and surgery produce significant results

I found this category of interventions the most straightforward and least surprising: medications to reduce appetite and surgical operations to shrink the size of your stomach are indeed highly effective, but they’re expensive and run the risk of side effects.

Weight loss medications have a long and troubled history. Amphetamines were popularly used to suppress appetite in the mid-20th century, but addiction and abuse proved disastrous. Phentermine and fenfluramine (fen-phen) was popular in the 80s, until we found out that it caused heart disease.

There are only a handful of drugs approved for obesity, and the FDA is pretty strict: a drug candidate needs to have a 1 year trial to demonstrate safety, at least 35% of participants need to lose 5% body weight or more, and that proportion needs to be 2x the placebo group. These standards ensure that approved medication efficacy is high (50-70% of people will lose at least 5% body weight). Unfortunately, none of the drugs have generics yet, so they cost between $200-300 per month.

Bariatric surgery is the last line of obesity interventions, typically reserved for patients with a BMI greater than 35 (e.g. someone who is 5'4" and weighs >205 lbs, or 5'9" and weighs >240 lbs). Surgeons use a few different techniques, but all of them seek to reduce the size of the stomach. The intuition is simple: a smaller stomach will hold less food and will more quickly start to stretch as you eat, triggering a sense of fullness.

Over 95% of patients will lose at least 5% body weight, so surgery may be the only intervention that can reliably produce meaningful weight loss. However, it’s not commonly used at this point - nearly 40 million American adults have a BMI > 35, but fewer than 250k bariatric surgeries are conducted every year. A standard lap band operation costs an average of $14k, and some insurers will cover the bulk of the cost.

Interestingly, though surgeons have been performing these kinds of operations for over 50 years, we still have a limited understanding of how exactly the surgery produces the observed weight loss - it doesn’t seem to be purely through the mechanical changes of the stomach (it probably also has to do with nerve signaling, hormone activity, bile acid and microbiome changes too).

5) Financial cost isn't everything

Paying more for weight loss help seems to work, and there are a variety of interventions along the spectrum depending on your budget and preferences.

The elephant in the room is that the relationship between financial cost and weight loss efficacy might be at least partially explained by motivation and readiness to make lifestyle changes. After all, if you're willing to pay hundreds or thousands of dollars to lose weight, you're probably going to see more success than someone who downloads MyFitnessPal for free. Studies control for this though: they recruit average overweight individuals who have been referred by their doctor, and they offer interventions for free, ensuring that their study population is a reasonable sample and not skewed towards the highly-motivated.

But it does pose a broader question. Given the cost of obesity (>$150B per year in healthcare costs), you’d think that any number of these solutions should be financed and deployed en masse by insurance companies and other payers. Why aren’t they? And if they are, why haven’t we seen any decline in obesity rates?

Convincing people to try a weight loss intervention isn’t trivial. If one day you receive a letter from your insurer inviting you to participate in a group weight loss coaching program, what’s the likelihood you would participate? What if I told you it would be scheduled at a local YMCA 15 minutes away - would you attend? And stick with it past the first session?

People don’t try effective weight loss interventions because there’s a third axis that matters: the non-financial cost. Whether it’s the inconvenience of attending a weekly meeting, annoyance at having to log every meal, hunger of sticking to a 1000 calorie/day diet of pre-packaged foods, or anxiety and pain of undertaking a major surgical operation - these costs dwarf the financial cost.

Many people who aren’t overweight fail to perceive these costs, perhaps because they’ve never experienced the same degree of physiological discomfort and psychological trauma from hunger, cravings, and living life with excess weight.

I like what John Walker, the founder of Autodesk, wrote in his book, The Hacker’s Diet. He compares our current view of obesity to what people might have believed near-sightedness was in the past - a defect of character:

One can imagine, before eyeglasses were invented, a culture that exalted those with 20/20 vision and disdained others who had difficulty seeing distant objects. Poor vision might be attributed to “flabby eyes,” resulting from a lack of visual exercise. Yet what distinguishes the near- and farsighted from those with perfect vision is but a minor difference in the shape of the lens in the eye.

Just as we invented eyeglasses and LASIK, we’ll need to innovate new solutions that minimize the non-financial costs of weight loss if any progress is ever going to be made.